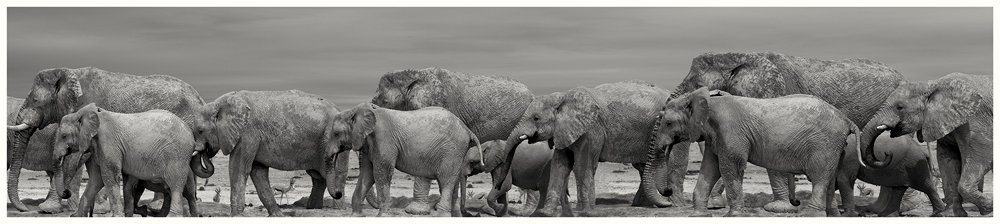

In an attempt to articulate the visceral potency of Christopher Rimmer’s photography, the author, Tony Park said Rimmer’s work looked so deeply into Africa’s heart that you could almost feel the heat and taste the dust.

Christopher Rimmer’s photography invariably evokes similar responses in the viewer. There are those who leave his exhibitions with tears in their eyes and those who feel somehow ennobled, yet humbled, by the images they have seen, as if the pathos and the splendour of these visions of human and animal survival, had touched their brow with an extraordinary brush of light.

Christopher Rimmer’s formative years were spent in South Africa during the 1970’s when the country was firmly in the grip of the Apartheid policies of B.J. Vorster’s National Party. He began taking photographs as a teenager and from an early age, his photography revealed a sophisticated insight into his environment that belied his youth. His work was published in South African magazines whilst he was still a teenager and work from his most recent exhibition, Spirits Speak, saw him shortlisted in London for the prestigious Black & White Photographer of the Year award.

I spoke to Christopher Rimmer over lunch in Johannesburg, just a stone’s throw from where he grew up.

—

Well I suppose I should ask how it feels to be back in South Africa. Does it still feel like home?

Yes it does. I’m always happy to be in South Africa. I travel here often. I left something of myself here when I left in 1982 and I re-connect with that whenever I return. The photography I have produced in southern Africa is also an expression of that re-connection.

Do you think that the fact your work ‘comes from the heart’, so to speak, is why people are drawn to your photography? There are many aspiring photographers who take photographs in Africa, why do you think your work has been so successful?

I seldom meet people who purchase my photography but on the occasions when I have they often tell me the photograph ‘speaks to them’ which I take to mean that there is something visceral occurring when the person views the image which is in truth, a mystery to me. I operate with a visual agenda when I’m working and I seldom, if ever, even think about the person who may end up hanging the finished print on their wall.

What do you mean by a visual agenda?

I mean that I have something visual in my head that I seek and I keep going until I feel I have captured it. Perhaps that explains why my work is so graphic; the image exists as a vision to some extent before it is captured. So I go out there in pursuit of visual ideas which I attempt to bring to fruition.

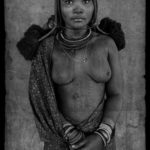

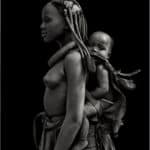

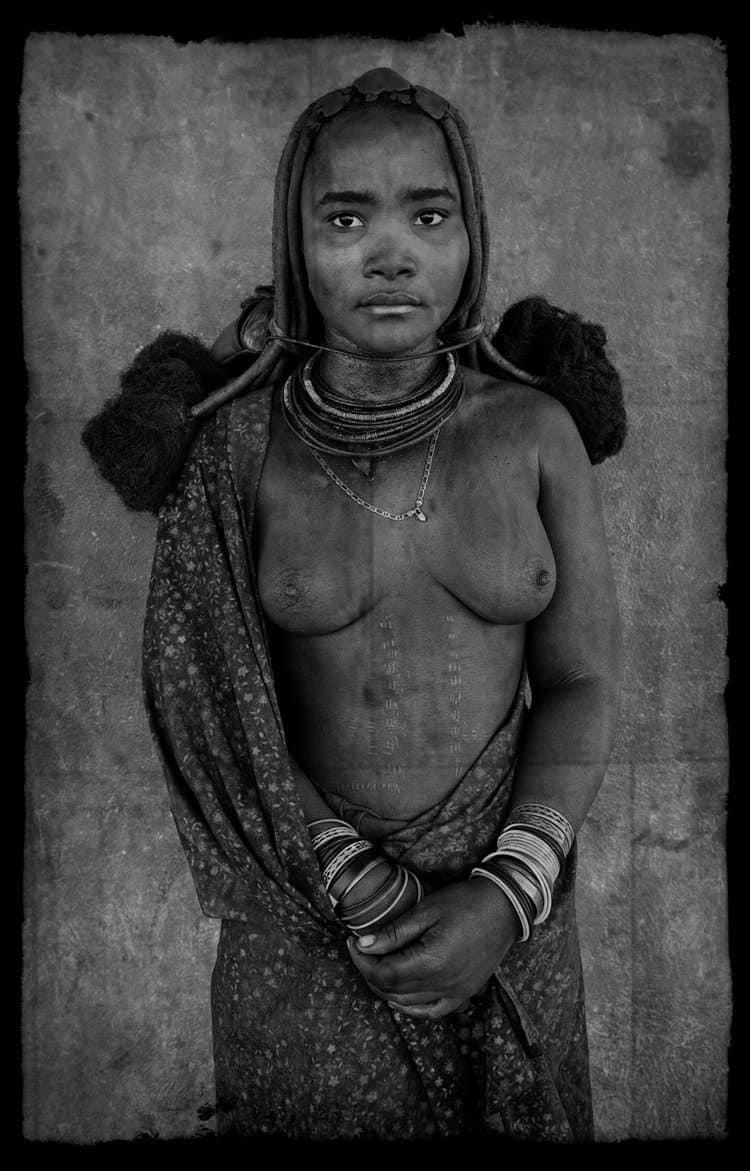

When Facebook removed your photographs of bare breasted Himba Tribal women, it became a news story. Did that upset you?

The Facebook thing didn’t really upset me although I think an organization as large as Facebook would benefit from a more sophisticated means of differentiating what constitutes art and what constitutes obscenity. What upset me was the debate that raged in some media about the images of the Himba women being patronizing and colonial.

I realize that this genre of photographing indigenous people is ideologically tainted, but I find it aesthetically compelling nonetheless. I think, as an artist, I should be free to explore this without a bunch of holier than thou, do-gooders suggesting that by doing so, I am revealing some concealed sense of superiority over my subject.

Do you find photography in Africa specifically problematic?

No more than anywhere else. There is more of a culture of paying for photographs in Africa, particularly in the urban areas which some people find a difficult thing to navigate. Certainly the quality of light in Southern Africa in places like Zimbabwe and Namibia is unlike anywhere else on earth. The work I did in Namibia has a particular signature to it that I know I would find impossible to replicate anywhere else and that’s down to the quality of light.

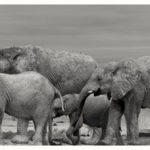

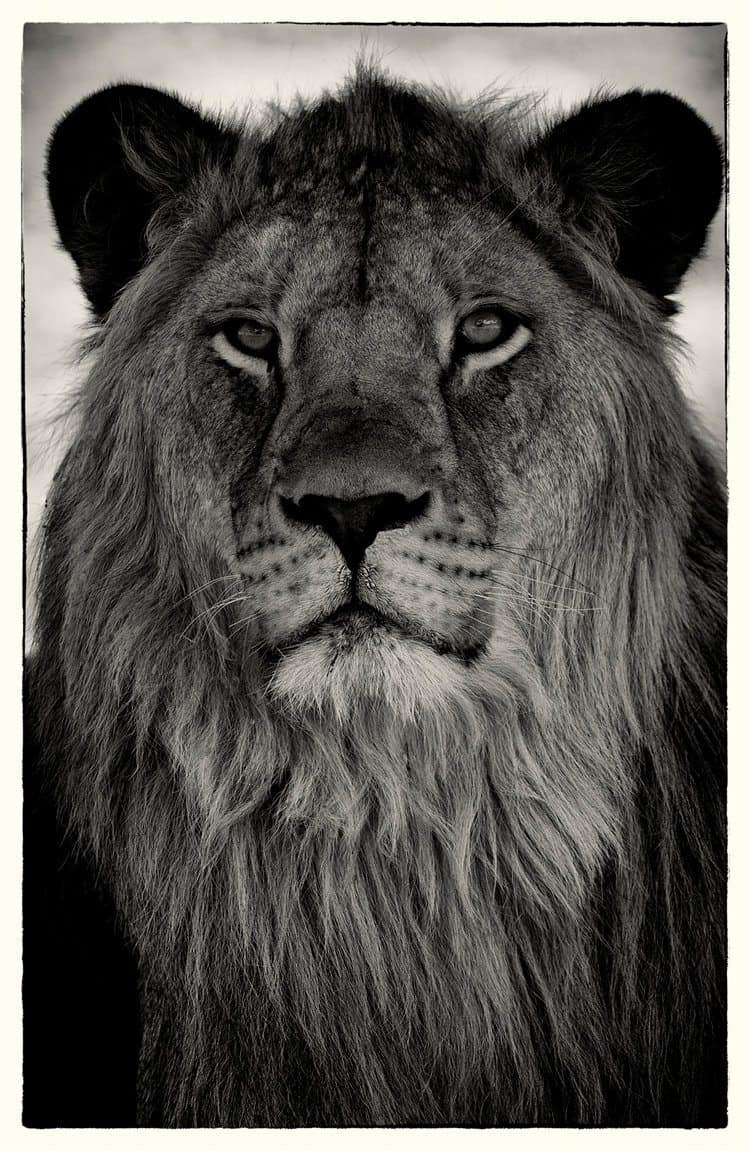

Your Wildlife Shots have an incredible level of detail. How close do you get?

I get asked that all the time and the short answer is very close. I only use short lenses. The quality comes from the fact that I use medium format. If you get in close with a good lens, you can get some great results assuming the light is good too. You have to balance it with staying safe though.

Do you attempt to promote conservation with your photography?

Obviously when people see my work, inevitable questions regarding the extinction of species and the destruction of traditional tribal culture through modernization are raised. I have always thought that if people could emotionally connect with what they see in my work, they would be encouraged to care.

When Lowveld Lion looks directly at you as he does, how can you not feel him asserting his right to exist? How can you not respect him a sentient being with whom we share this planet? Shouldn’t we be doing more to ensure he survives? I think we should.

What’s on for Christopher Rimmer the remainder of 2013?

Well I’m working on some new material which I intend to exhibit next year. I have been photographing the ghost town of Kalmanskop in Namibia and making massive colour C Type prints. I was over in Namibia earlier this year and I’m heading back in August to continue. I am exhibiting work at Photo Menton in France and a few other festivals in the E.U. over the northern summer.

Thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule to speak to me.

—